My essay “Home Rule: Equitable Justice in Progressive Chicago and the Philippines” has been published…

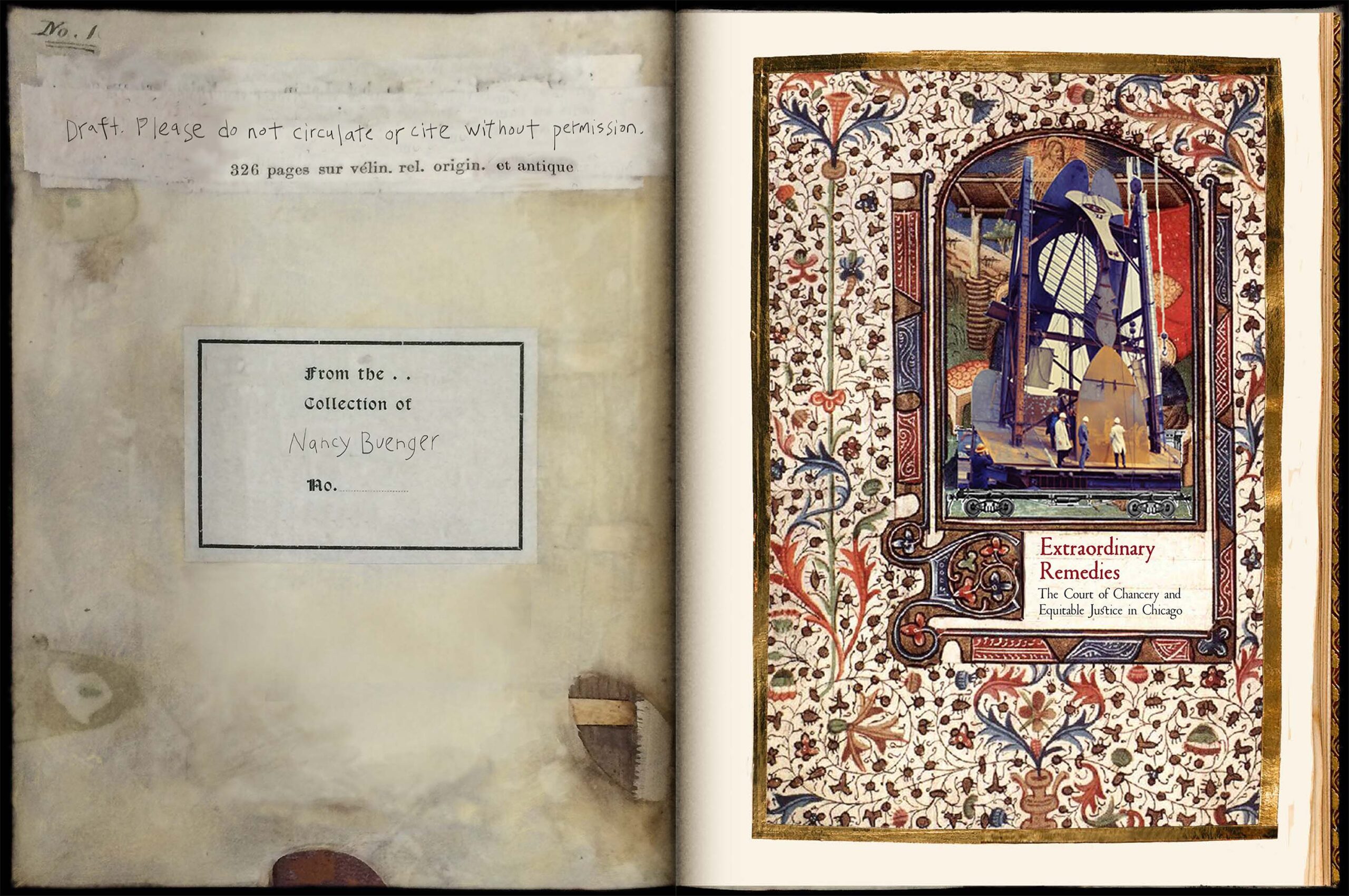

extraordinary remedies

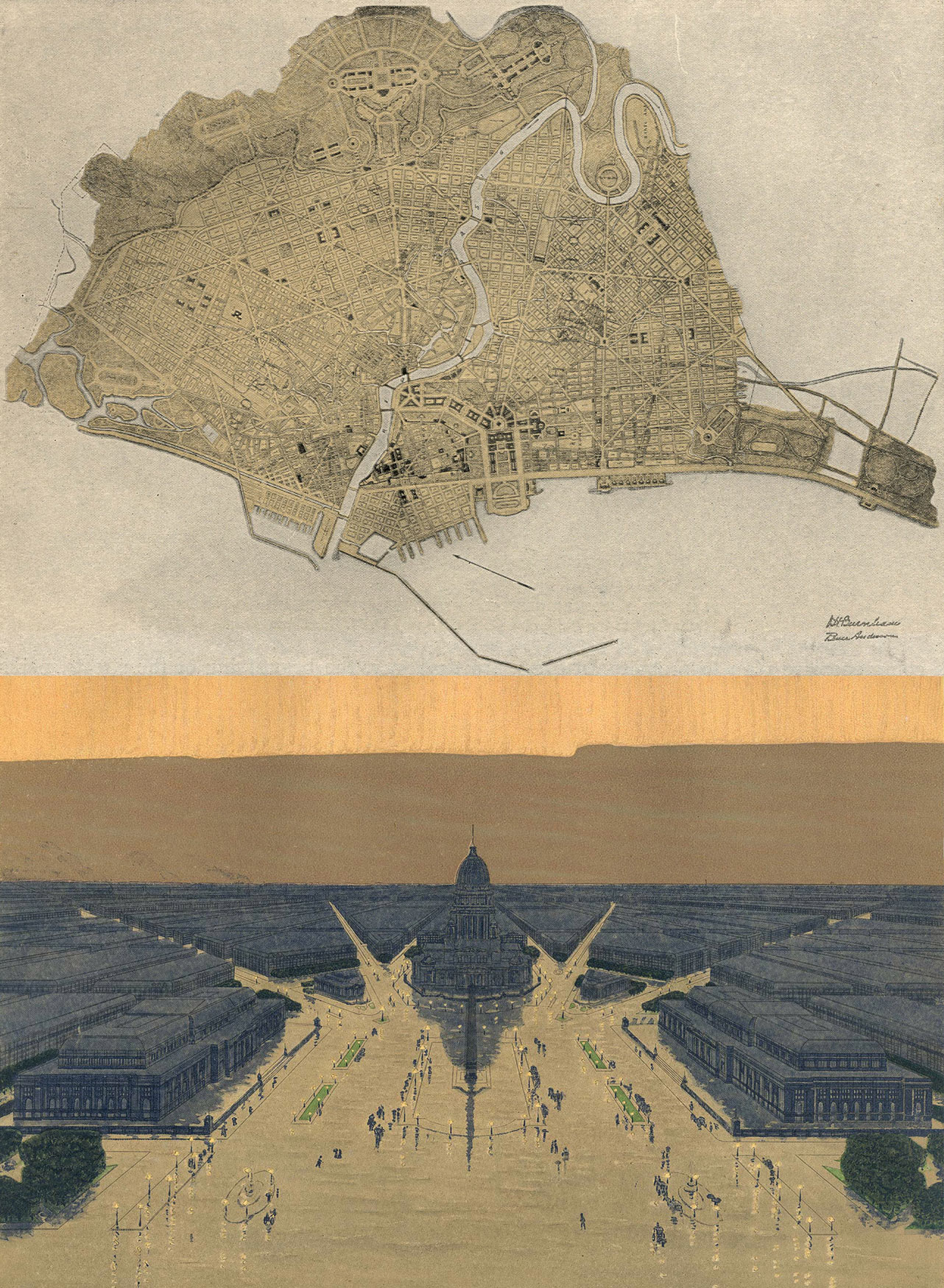

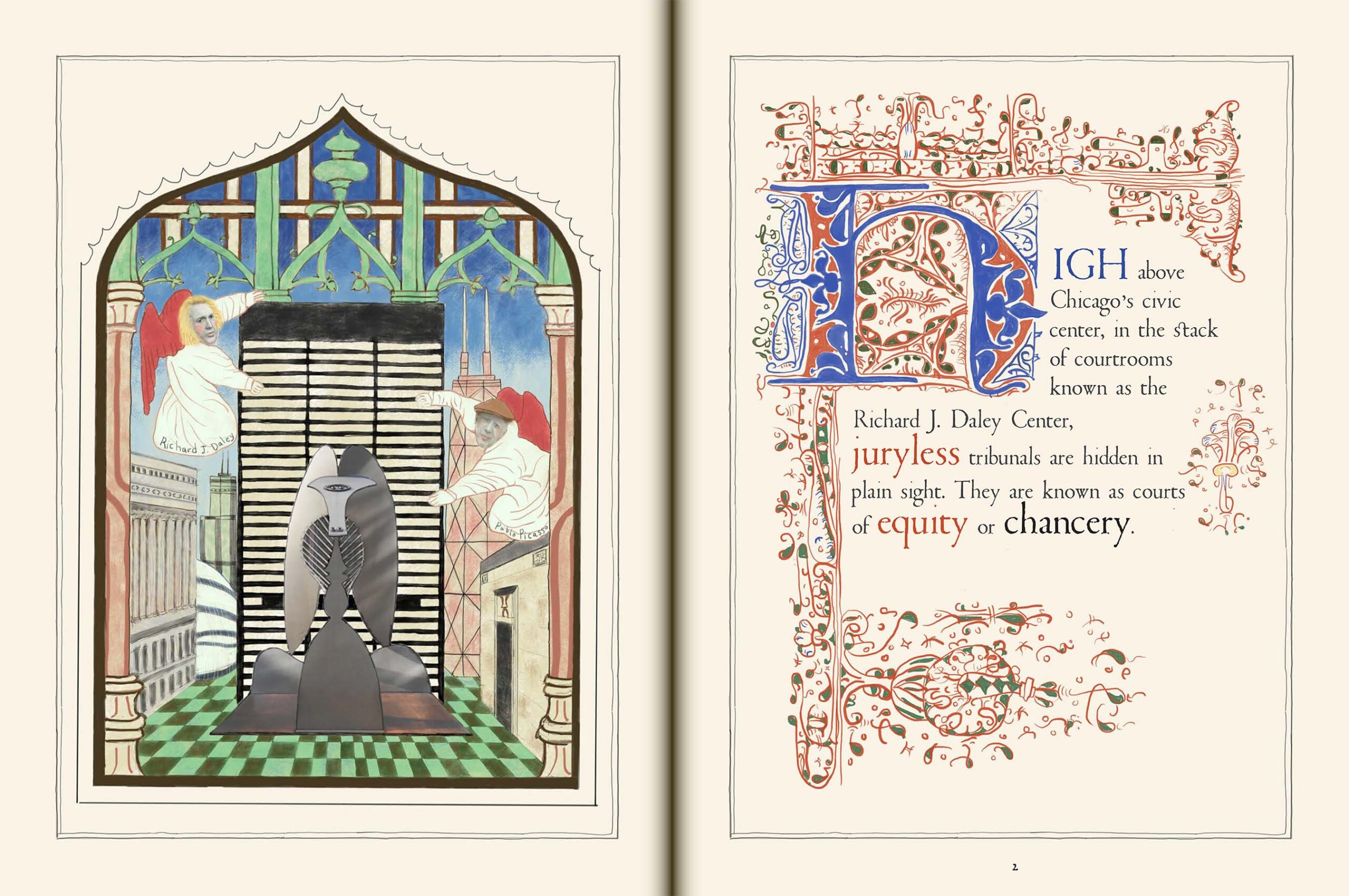

I’m currently remediating my book project Extraordinary Remedies: The Court of Chancery and Equitable Justice in Chicago as a graphic history. As I engage more deeply in public projects, I am decidedly less interested in publishing a traditional monograph. And as a scholar with deep museum roots, I find it difficult to tell this story without all the other stuff—objects, images, sounds, performance—essential to exhibitions. In the best of all possible worlds, I would publish Extraordinary Remedies as a multimedia digital project with an academic press. In the meantime, a hard-copy graphic history may suffice. Images will be a central device for linking past and present, siting a metropolitan legal history–ecclesiastical, colonial, and municipal–in Chicago’s Cook County court system. I’ve been invited to submit the graphic manuscript to the University of Chicago Press, we’ll see what happens.

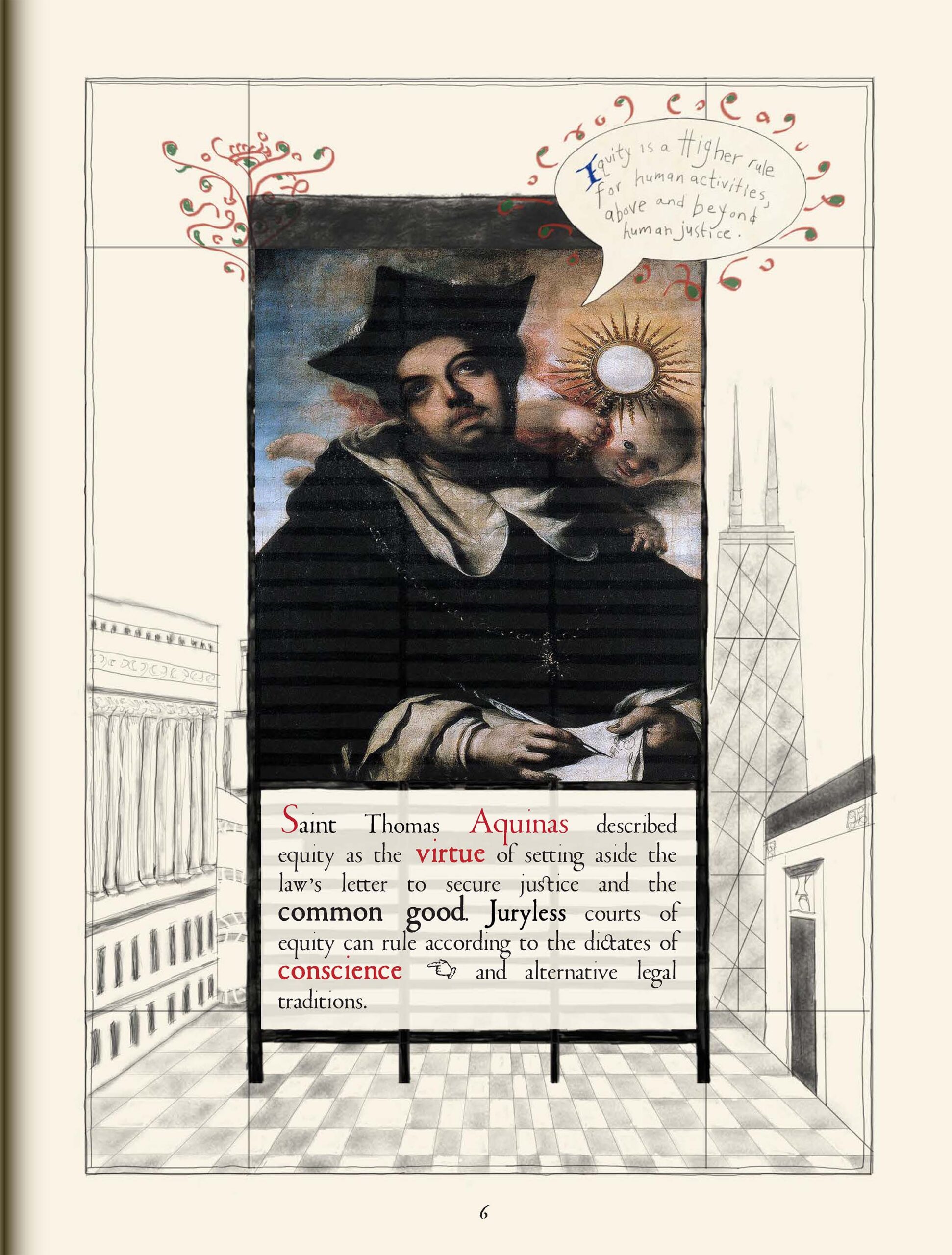

Extraordinary Remedies nests local and global state building, focusing on Cook County’s distinctive chancery, the largest in the present-day United States. Chancery or equity—the terms are used synonymously—is a juryless administrative court that can set aside the law’s letter and craft discretionary remedies from the dictates of conscience and alternative legal traditions. A Roman canonical heritage, the court specializes in administering quasi-sovereign populations lacking full legal capacity. Historically, these have included married women, wards, slaves, indigenous peoples, blacks, territorial residents, those deemed mentally or physically deficient, industrial servants, juveniles, and aliens.

Equity poses a central paradox in a nation dedicated to the rule of law and the equality of sovereign individuals. It allegedly met an early US demise, inspiring due process protections and lingering as an extraordinary legal remedy. It is undocumented as a distinctive metropolitan jurisdiction specializing in quasi-sovereign populations. Yet by 1940 equity was the default jurisdiction in civil and non-felony criminal courts nationwide.

Equity’s elusiveness is a measure, in part, of its present-day ubiquity. Equitable remedies are now ordinary rather than extraordinary in vast areas of American law, and discretion pervades the US justice system. Jury trial rights remain enshrined in state and federal constitutions, but their applicability is a complex equation, and trials themselves are vanishing.

According to Saint Thomas Aquinas, “we remember less easily those things which are of subtle and spiritual import.” Memory was an essential element of prudence for Aquinas, a well-advised calculation of the future derived from knowledge of the past. It is prudent to remember equity, to grapple with its paradoxical potential, acquiring knowledge of the past to advise our future calculations for the common good. Illuminated medieval manuscripts, the design inspiration for Extraordinary Remedies, were intended to cultivate the art of memory. Aquinas advised the use of extraordinary images that arouse wonder for this purpose, “as the soul is more strongly and vehemently held by them.” Such images were to be arranged on loci or particular places to enhance our memory.

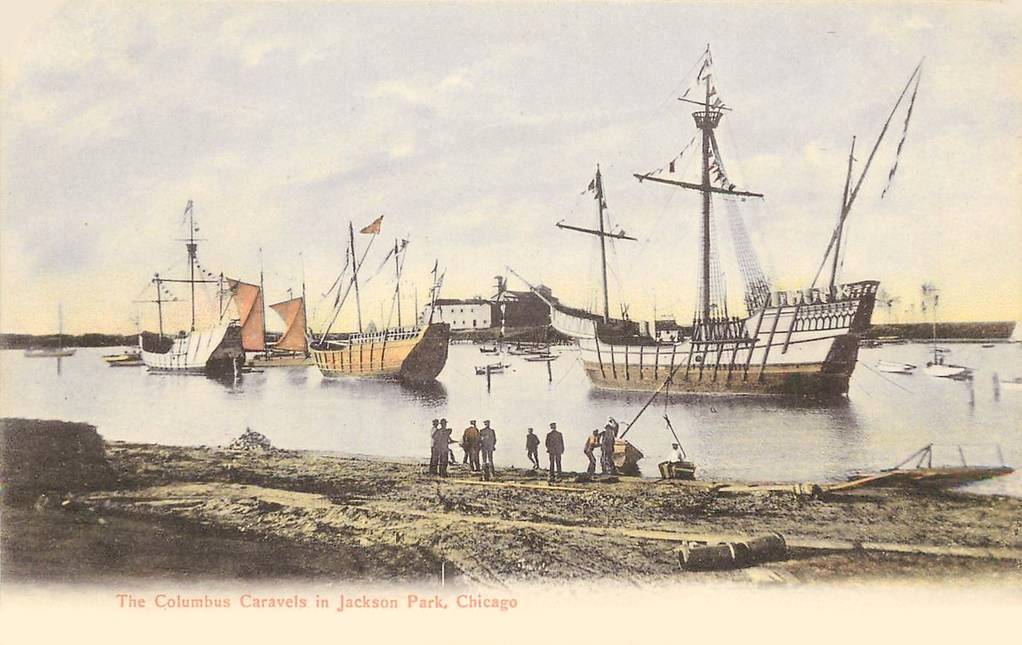

Practicing the art of memory in Chicago reveals equity as a powerful metropolitan engine rather than an emasculated legal standard. Beginning in the Northwest Territory, I focus on Chicago—the Metropolis of the West—interweaving US judicial interventions in the Americas and Asia. A host of legal actors—including women, blacks, and indigenous peoples—expanded equity’s criminal jurisdiction, replicated its administrative machinery, and set aside the law’s letter, experimenting with alternative legal remedies. Ultimately, the court emerges as a cornerstone of American understandings of the rule of law. Embodying the Christian, imperial, and constitutional authority to decide on the exception, equity powers American state expansion, at home and abroad.

Picasso Sculpture and Cook County Courthouse, Richard J. Daley Civic Center, Chicago