home rule

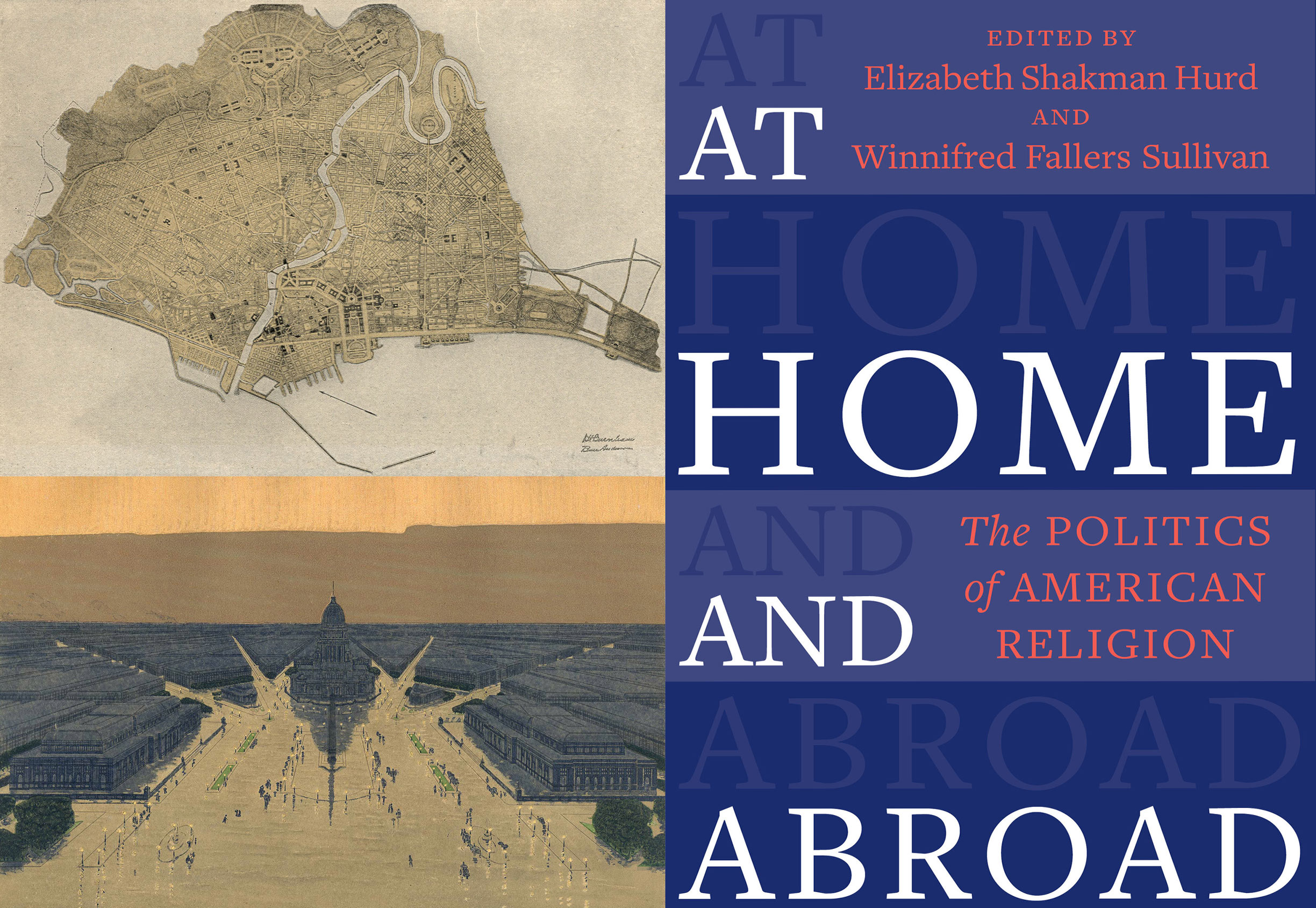

My essay “Home Rule: Equitable Justice in Progressive Chicago and the Philippines” has been published in At Home and Abroad: The Politics of American Religion, edited by Elizabeth Shakman Hurd and Winnifred Fallers Sullivan. I consider metropolitan state building in 1900 Chicago and the Philippines through the lens of home rule, or the governance of dependents and other quasi-sovereign populations lacking full legal capacity.

Left: Plans for Manila (top) and Chicago (bottom), Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, Plan of Chicago, 1909. Right: Cover image, At Home and Abroad.

Home rule was a Progressive mantra in Chicago and the Philippines, sites of significant US judicial reconstructions at the turn of the twentieth century. A richly ambiguous international agenda, home rule is commonly conflated with local and limited democratic governance in the United States. In Progressive Era Chicago and the Philippines, home rule drew deeply on the extraordinary power and expansive administrative capacity of equity, a court specializing in the guardianship of those who “have not discretion enough to manage their own concerns.”

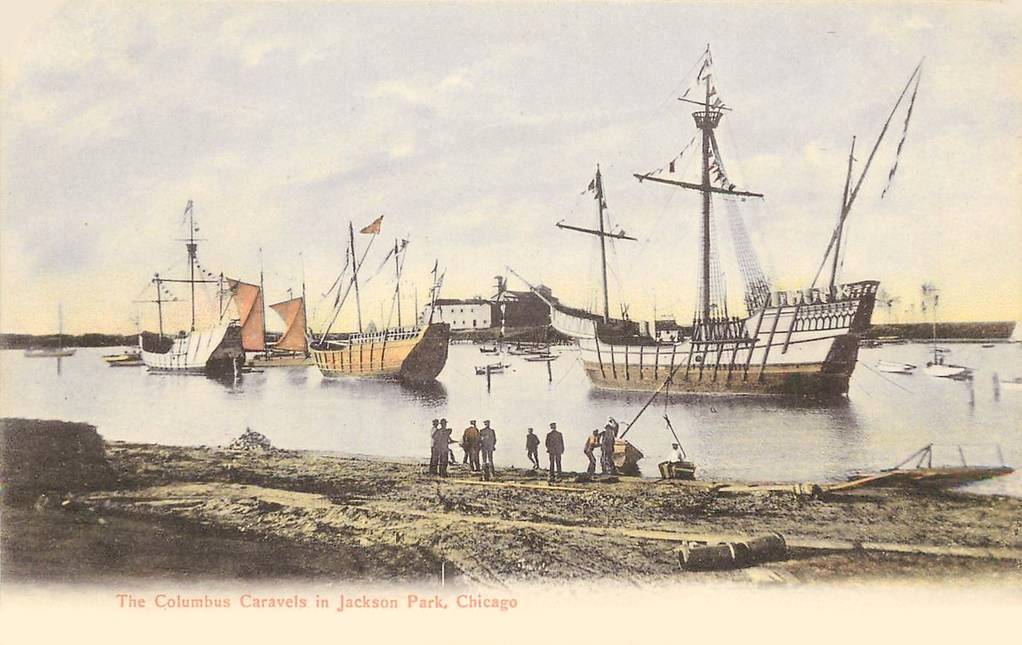

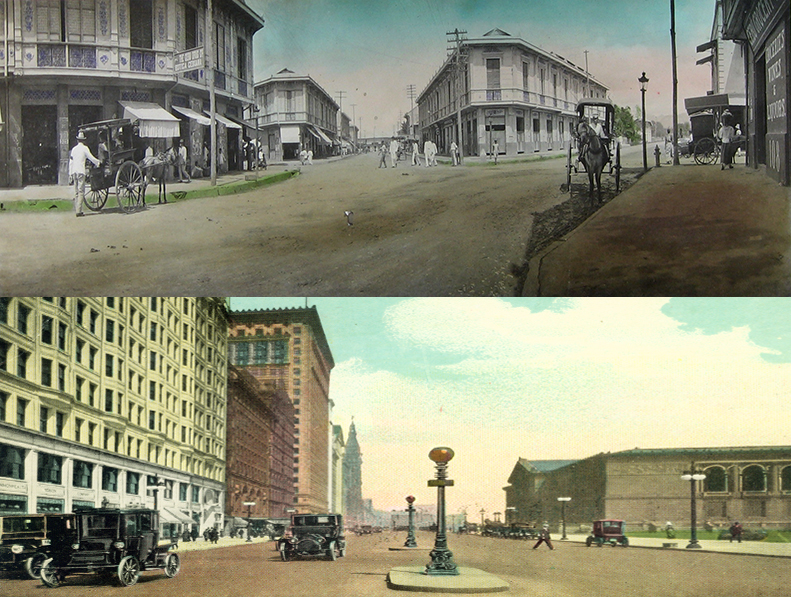

1900 Manila (top) and Chicago (bottom)

Both Spanish and Anglo-American courts have historically relied on equity, a Roman canonical heritage, to administer domestic and colonial dependents. Equitable courts can set aside the law’s letter and craft extraordinary legal remedies according to the dictates of conscience and alternative legal traditions.

St. Thomas Aquinas described equity as the virtue of setting aside the law’s letter to secure justice and the common good.

In June 1900 US Judge William Howard Taft arrived in the Philippines—the most strategically important spoil of the Spanish-American war—to establish “the largest measure of home rule.” His first directive was to organize municipalities in which the natives might manage their local affairs “to the fullest extent of which they are capable.” In collaboration with Filipino jurists, Taft and his Philippine Commission revamped the insular judiciary, specifying juryless criminal proceedings “analogous to those in a court of equity.” The juryless insular courts sparked heated national debate and fear that the constitutional rights of all US citizens were imperiled.

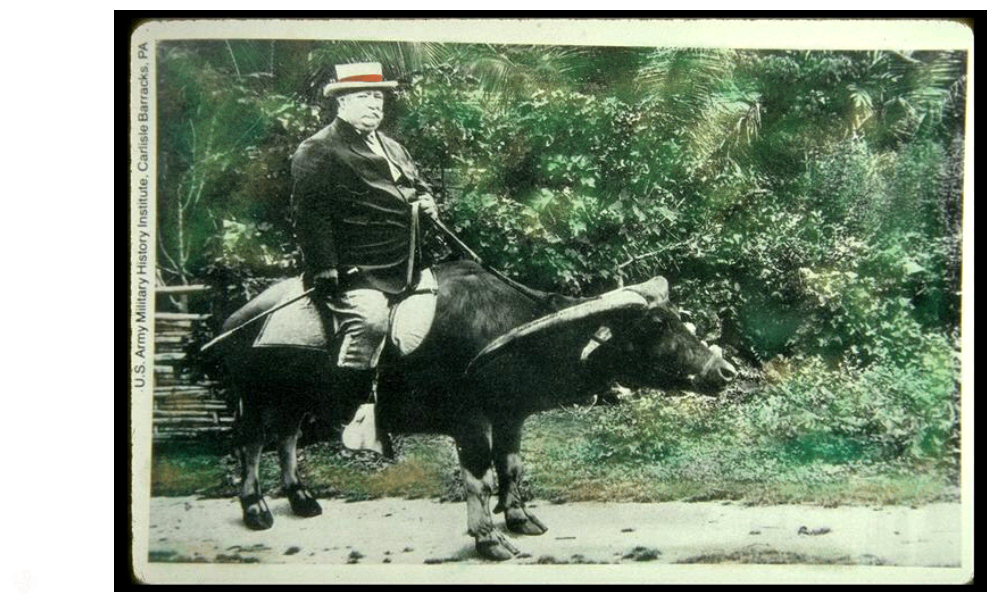

Philippine Governor General William Howard Taft seated on a water buffalo, c. 1904

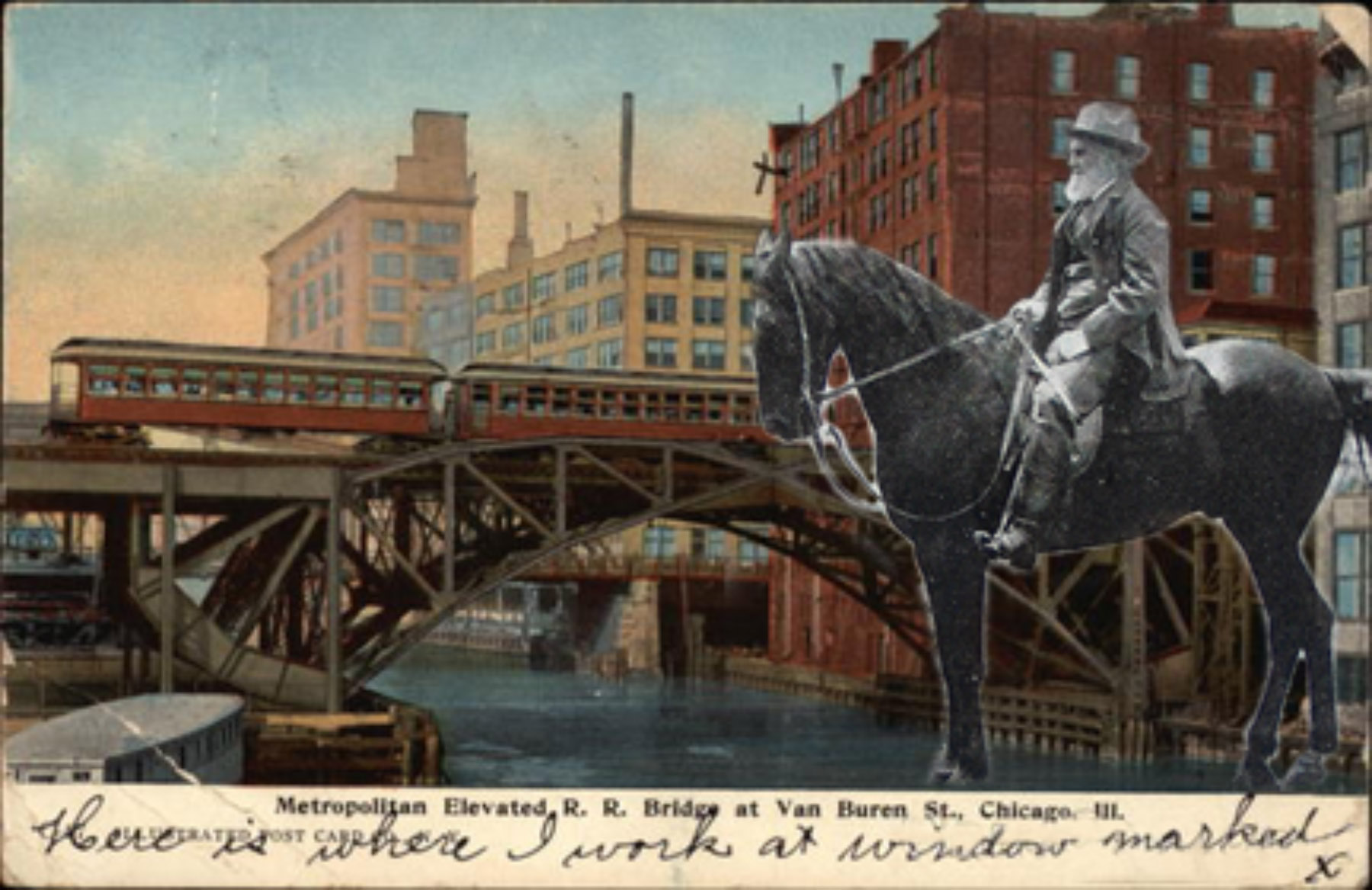

In 1900 Chicago—the fastest-growing US city—the Civic Federation launched a home rule campaign for municipal self-governance under the direction of Cook County Chief Justice Murray Tuley. Revered as the city’s “Dean of Chancellors,” Tuley presided over the circuit court chancery, a distinctive equity jurisdiction that persists to the present day. He initially opposed municipal home rule, arguing that Chicago, like the Philippines, was not yet capable of self-government; there were times when the state must check evil tendencies in its municipal child. But the Civic Federation persuaded the chancellor to direct enabling legislation for a new city charter and planning for a municipal court that adopted juryless criminal proceedings analogous to those in a court of equity. The Chicago Municipal Court was championed as “the pioneer modern” archetype for judicial reform. In consultation with Taft, Chicago jurists developed plans for model juryless courts that were adopted nationwide.

Chicago “Dean of Chancellors” Murray Floyd Tuley

The national outcry over juryless US insular courts stands in striking contrast to the accolades for Chicago’s juryless municipal court. Both the insular critiques and paeans to Chicago modernism masked a long-standing reliance on equity to administer dependents and other quasi-sovereign populations at home and abroad. Equity’s obscurity is in keeping with what has been described as the strangely self-denying and extraordinary power of the American state. A constitutionally vested judicial power, equity is virtually undocumented as a US state and territorial court in scholarly studies. Yet by 1938 equity procedure predominated in federal civil courts and, soon thereafter, state courts nationwide.

Chicago City Hall and Cook County Courthouse, c. 1910

Equity’s elusiveness is a measure, in part, of its present-day ubiquity: extraordinary remedies are now ordinary in vast areas of American law. Equity is also at odds with national narratives championing the rule of law, trial by jury, and the equal rights of sovereign individuals. But these narratives are at odds with the present-day US justice system, where prosecutorial discretion is pervasive, less than three percent of all cases proceed to trial, and people of color are disproportionately criminalized, imprisoned, and executed. Embodying the Christian, imperial and constitutional authority to decide on the exception, equity powers American state expansion, at home and abroad.

Manila courtroom, c. 1910